Today I want to delve a little deeper into the nexus of the strands of the dance medium. In Unintentional Juxtaposition in Tribal Fusion dance I looked at the nexus of the strands on a macro level. But I'd like to zoom into one aspect of this nexus. I suggest reading this article first to give you a bit more of an overview on this topic, yet it is not necessary in order to understand the content in today's post.

In Valerie Preston-Dunlop's book Dance and The Performative, there are 5 strands that we talk about when we are talking about the dance medium: sound, movement, performer, space and audience. We also talked about the relationship (or nexus) between these strands. This relationship can be juxtaposed, integrated or coexisting.

Integration of Sound and Movement

As tribal fusion dancers, the relationship between the sound and the movement strand is of course very important. In fact, often you will hear teachers say things such as 'embodying the music', 'becoming the music', 'letting the music move you',... These are all terms we are very much familiar of, I am sure. When someone says about a dancer that they have good musicality, they mean that they are embodying the music very well: the music becomes visible through the movements in their bodies.

A good example of a dancer that has good musicality is Violet Scrap. When Violet dances, she brings attention to the music in such a way that I discover layers within the music that I wasn't even aware of. Her use of movement quality and dynamics is so rich that it brings out the different textures that the music holds, and she decides which layer she wants you to listen to. The relationship between sound and movement is completely integrated.

So how does one embody music? Many people would say that this is an intuitive thing, but I like to dissect something that seems intuitive or that seems abstract into something tangible, just for the sake of it. In order to dissect, we have to somehow translate the sound strand into the movement strand. For movement, I would like to focus just on space and dynamics for the time being.

- different volumes in music can be translated in different volumes of movement, meaning that prominent, loud elements in the music reflect with big movements of the body (spatially) and with using strong movement (dynamically) - whereas sounds that are hardly noticeable can be translated as small body isolations (space) with a softer quality (dynamics)

- low sounds invite movements that are going downwards (space), when higher pitched sounds invite upwards movement. For example: we intuitively want to place a hip drop or chest drop on a DUM and a hip lift or chest lift on a TEK.

- monotone long notes (where pitch doesn't change, i.e. the bass sound bagpipes make) invite continuous movement (dynamics) as well as movement travelling in one direction (linear) or in one plane.

There are many more ways of thinking how music translate into movement, feel free to add some ideas into the comments section.

But movement doesn't always have to be a litteral translation of the soundscore. I personally like to think of the body to be an extra layer within the music, sometimes connecting to one instrument, sometimes another and sometimes creating an instrument on its own that somehow compliments with the music. It allows a bit more freedom, as I don't feel slave to the music, but it's still integrating sound and movement.

Postmodern dance ideas often happened through rebellion against the norm. In ballet for example, the movement always came after the music. The music was composed and then choreography was set to this music. Dancers felt that dance never stood on its own, that movement could not be its own art, and that movement was therefore slave to the sound strand. So dancers began to explore the idea of movement standing on its own, either by using silence or by creating movement first and bringing sound in later.

I like what Mira Betz has done in this video (it won't let me embed it here for some reason) She has connected the sound of her heartbeat to a speaker to make her audience listen to her heartbeat live, while she is dancing to the beat of her own heart. Sound and Movement strand are therefore still integrated, yet as opposed to what most tribal fusion dancers do (Sound first, Movement later) it is the movement that is controlling the sound (by slowing down her movement she slows down her heartbeat and vice versa) I think this is a very interesting concept on the relationship between sound and movement.

Juxtaposition between Sound and Movement strand

dancing in silence:

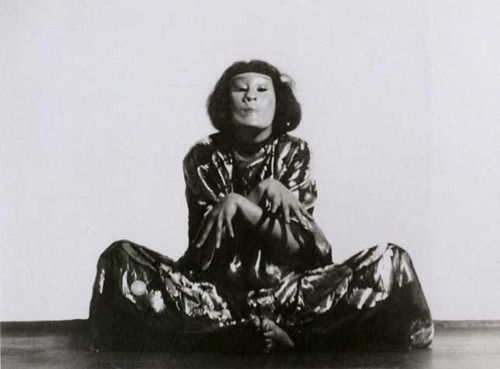

One of the first dancers ever to use the idea of dance in silence was Mary Wigman in her Witch Dance. (There is no video of this, yet there IS video of a later version of the original Witch Dance, yet this video does have a soundscore) In its time, it was the most contemporary thing anyone had ever done. It was just not done to NOT dance to music, so it was controversial and fresh. But apart from the controversy, what I find interesting is that dancing in silence strips the dance down to just the movement. Sound can sometimes provide distraction that doesn't always add to a performance, sometimes it detracts. I would say that the relationship between sound and movement here is juxtaposed. Because the sound of silence invites stillness as opposed to movement, therefore there is a juxtaposition between the two strands.

moving to soundscore:

Another (perhaps clearer) example of juxtaposition could be when a dancer softly undulates to a song that invites dynamic, strong and large movements. Or vice versa, the song has a continuous, soft quality while the dancer manically shakes and vibrates through the space. There is a clear opposition between sound and movement in that case. Often juxtaposition invites an uneasiness with the audience, something doesn't sit quite right. I believe this can be an excellent tool. Say that I were to make a dance about i.e. being an outcast. the fact that sound and movement are juxtaposed can be related to the idea of feeling like you don't fit in. At the same time, your audience will perhaps feel alienated from you because they cannot relate to the experience, therefore mission is accomplished as the artist is truly bringing the idea of the outcast to the performance.

Coexisting relationship between sound and movement

A coexisting relationship means that there is no connection between the two strands, they just live side by side. Whereas juxtaposition is literally trying to do the opposite of what is expected, coexisting strands bare no relationship whatsoever.

The best example of a choreographer that uses coexisting strands is of course Merce Cunningham. I saw my first Cunningham piece in 2004. I hated it. I wanted to walk out of the theatre. Why? because I didn't get it. The Kinaesthetic Gap was so big for me that I wasn't getting anything out of the performance. I knew Merce was an important choreographer but I really didn't get why, looking at that performance. But the day after we had a workshop with one of the Cunningham company members and I learnt the process behind the product/performance, I understood why he was one of the most important choreographers of the 20th century. He completely broke the relationship between sound and movement by asking John Cage to write a 90 minute soundscore while he (through the use of chance - i.e. rolling a dice) works with his dancers on a 90 minute movement score. Only during the dress rehearsal would sound and movement be put together. Cunningham was not interested if it worked or didn't work, he was interested in taking away the expectation of what works and what doesn't and that was his reflection of life: nothing means anything, everything is just stuff that happens.

Having that background knowledge changed my relationship on how I watch a Cunningham performance.

But is it still Tribal Fusion?

The idea of dancing to silence or to make the sound and music strand juxtaposing or coexisting is clearly not new in contemporary dance, yet in tribal fusion it's a fairly new concept. The question is: if tribal fusion is in definition about embodying the music, will it still be tribal fusion if we were to dance in silence, or if we were to juxtapose the movement and sound strand? Perhaps not, but perhaps the exploration is still worth having. We can figure out what to call it later...